When strangers meet….

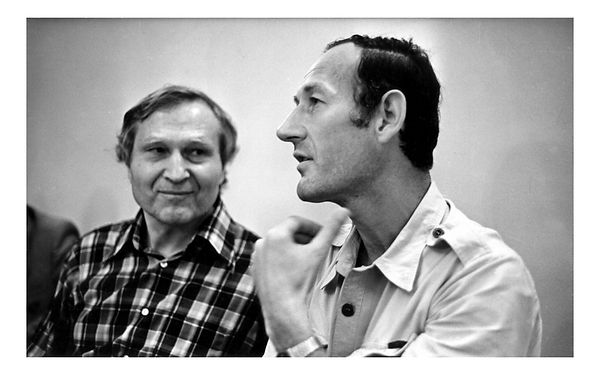

In 1989, during the Cold war, I met Vakhit, a Muslim screenwriter from Tataria USSR, with an idea to dispel some of the misconceptions of the other. I came to the Soviet Union for one month (after which my Tatar friend came to Canada for the same period, being hosted in our respective homes) at a time in human history when we had to get to know the stranger as a necessity for the human survival of our civilization. (Does that sound similar to 2017?).

As an anthropologist, in the early 1960s, I studied the Cree and Saulteaux peoples of Saskatchewan and soon discovered that our attitude is an important ingredient for effective communication and human understanding. Becoming friends requires overcoming negative images of the other and dispelling fear and misunderstanding of the unknown. Rubbing shoulders with our neighbour and stepping into the shoes of the other are useful metaphors in working across cultural boundaries.

When strangers become friends, as with Vakhit and I, we were deeply affected. Our lives were changed forever. I experienced this first-hand in Moscow, Kazan, Naberezhnye Chelny, Elabuga, Nizhniy Kamsk, as well as Ottawa, Toronto, Hamilton, Montreal, and Saskatoon. Doors were flung open as photographers, yachtsmen, hikers, teacher, artists, students, professors, public school administrators, religious leaders, union organizers, peace workers, writers, and even millionaires have come forth to meet the international stranger.

n Kazan, I met Misha and Evgeny and on their yacht Tempest 04 I spent an adventurous two-day boat trip on the Volga. Living together gave me time for face-to-face exchange on perestroika, glasnost, Stalin, religion, the nationalities question and more. Therein, I felt like Saint Exupery’s fairy tale figure of Little Prince who travelled the planets and came to Earth, where he learned finally, from nature, the secret of what is truly important to life.

As a traveller, I learned about the beauty of nature that transcends political boundaries and ideologies. Its colours, shapes, and sounds decorate our gaze and rejuvenate our bodies and minds. That beauty is precious, yet vulnerable to destruction if we pollute our waters, air and soil, and if fail to work cooperatively and sensitively as one family on our common planet.

From Vakhit, I learned that cleanliness is a cultural trait of the Tatar people. When you enter their home, you take off your shoes and are offered a pair of slippers. I have used this practice in my Canadian home.

More profoundly, from Murat, Bulat and Alexei, I learned that war is a human tragedy that few of us in the West can relate to. We need to acknowledge the fact that the Russian and Soviet peoples lost over 27 million in defending themselves during WWII.

I learned that gift-giving is an old tribal custom that has persisted through the centuries and has transformed strangers into friends. On my departure home, Vakhit and his wife Galiya presented me with a beautiful handcrafted woolen rug.

From strangers and newfound friends I learned that diverting money from the arms race can provide us with all the infrastructure we need, the architecture, clean water, universal education and free health care to make life livable and make peace possible in the world. Our human family aches for that shift in evolutionary thinking.

Opening doors with strangers is a good first step in this thinking by peacefully bridging two or more realities on Planet Earth.

By Koozma J. Tarasoff, Ottawa, Ontario. Anthropologist, ethnographer, historian, writer and peace activist. July 4, 2017.